Discover more from Oxymoron

Are we trapped in the Jevons paradox?

Over the past few weeks I've been working on a Theory of Change for Wholegrain Digital, mapping out how our work improving the efficiency of websites helps reduce the environmental impact of the web. It’s been a thought provoking exercise and I’m grateful to Fiona Ras-Jones for guiding me through the process.

The Theory of Change is essentially a logic diagram explaining how specific actions as an organisation will help address a problem in the world and deliver positive outcomes. Part of the process is to state any assumptions in the model and ensure that they are reasonable. I’m happy with all of mine apart from one, and it’s giving me a bit of a headache. It’s this:

That greater efficiency will reduce emissions and not drive greater consumption

You might be thinking that this sounds like an obvious statement. Of course greater efficiency will reduce emissions. Why would it possibly drive greater consumption?

To answer that, we need to take a trip back in time.

Journeying back to 1865

In the smog filled cities of Britain in the 1800’s, it was coal that was the real power behind Britain’s new industrial economy. Steam engines, powered by the burning of coal were at the heart of the revolution and some economists began to worry about how sustainable this new economy might be. Yes, coal had unleashed huge economic opportunities, but it had also created a dependency on coal, a finite resource that would eventually run out.

While some economists were relaxed in their estimates that Britain had ample coal reserves, others urged caution and the need to use coal more efficiently.

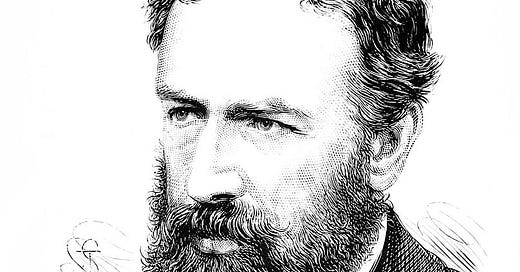

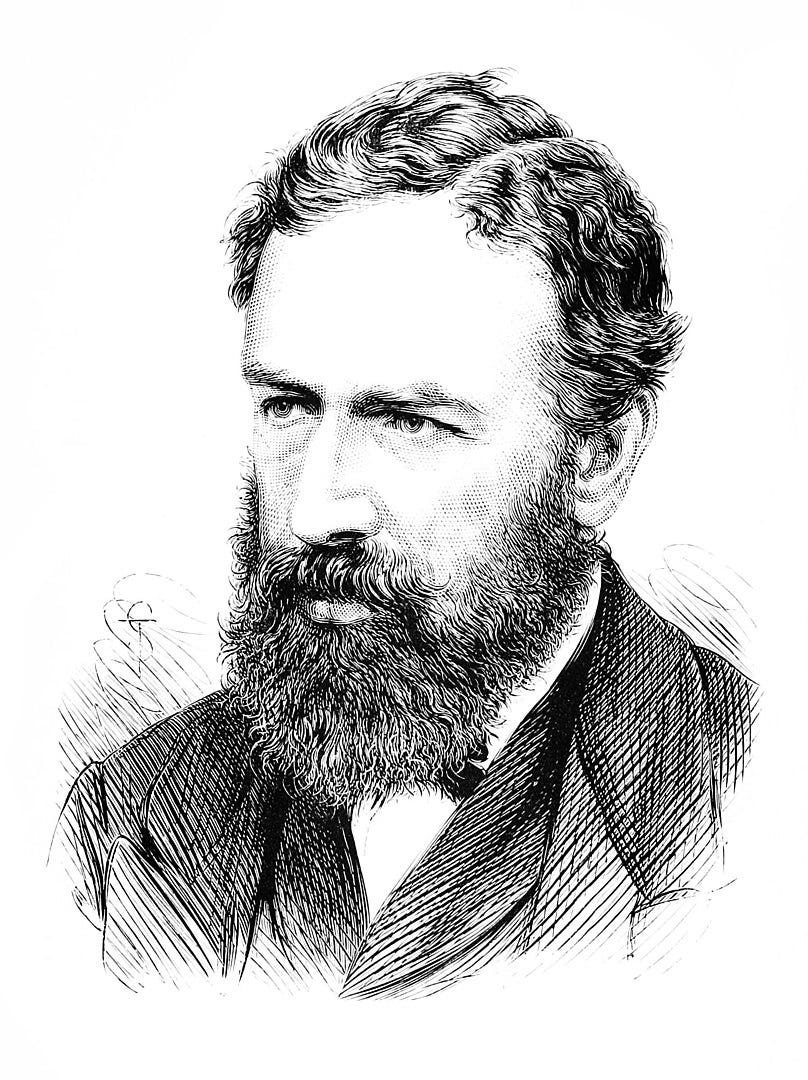

One economist however, disagreed with both sides. William Stanley Jevons was an outlier among the economists of his day and professed that while Britain’s dwindling coal reserves were of concern, developing more efficient steam engines was not the solution. He published a book in 1865 titled ‘The Coal Question’ and in it he stated:

It is a confusion to ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.1

He had observed that the introduction of James Watt's more efficient steam engine design had increased Britain's coal consumption, not decreased it.

His observation was that while improving the energy efficiency of technology does directly reduce the energy consumed by specific processes to do the same amount of work, it also creates a rebound effect. More efficient technology reduces the cost of production, which then brings down the cost of goods and encourages greater consumption. Furthermore, it opens up possibilities to use the technology (in this case steam engines) for new applications that were not economically viable in the past. It can also have an indirect rebound effect by fueling economic growth.

He argued that if we are not careful, the increased consumption caused by the rebound effect can equal or even exceed the initial efficiency savings when viewed across society as a whole. This concept became known as the Jevons paradox.

Back to the future

That was back in the 1800’s, but zoom forward to the 21st Century and we must ask whether the Jevons paradox still applies.

While the paradox is still debated, a number of modern studies have found it to be true. In the digital sector where I work, it is as plain as day. The energy efficiency of data centers, telecom networks and digital devices has increased immensely in the past 20 years or so, yet the total amount of energy consumed by digital technology keeps rising. Digital technology is now estimated to be responsible for 2.1-3.9% of global greenhouse gas emissions2, more than the aviation industry.

If you work in the digital sector and have your eyes open, the reasons behind this growth in consumption are not a mystery. As computers and networks get faster and cheaper, creative people invent new ways to consume the network capacity and computing power that they have at their finger tips - bigger pictures, animations, online gaming, streaming TV on demand, the metaverse! Not just that, but cheaper more powerful technology also removes the incentive to be frugal.

So on the one hand we have made our technology more efficient, but on the other hand we have increased demand for the technology. The paradox is that environmental sustainability requires resource efficiency without an increase in consumption. We are stuck in a loop.

Heresy!

Although the Jevons paradox is fairly well known in environmental economics, it is also fairly widely ignored. The problem is that accepting the Jevons paradox sounds like it would mean giving up on resource efficiency, which from an environmental perspective sounds like heresy.

If true, the paradox seems to undermine a large number of environmental initiatives. At first glance it leaves us with only two choices. Either bury our heads in the sand and ignore the paradox or accept the paradox and give up on energy efficiency, despite having no clear alternative.

But maybe there is another way. Maybe we should do neither of the above. Maybe we should face the paradox head on and look for a way to break out of it.

Can we break free of the paradox?

I’m going to tell you up front that I do not have a solution to the Jevons paradox. Very clever people have been thinking about this for about 150 years and struggled to find a solution, but we must find a solution nonetheless.

Some interesting schools of thought to consider are as follows:

The paradox is not universal

Some people argue that the Jevons paradox only applies in some circumstances and is therefore not a fundamental problem. The distinction is generally made that it only applies in markets where demand is elastic, meaning that demand increases as the cost of the product reduces. That sounds logical, but there are a couple of potential pitfalls.

The first is that it ignores the secondary rebound effect, where cheaper goods lead to economic growth and greater consumption more broadly, even if not for the same products. The second is that in reality there are very few goods that have truly inelastic demand. Examples often cited include petrol and diesel, prescription drugs, tobacco, salt and potatoes. Yet with the exception of salt, I have seen arguments that even these might be subject to significant rebound effects.

This is an area to study, to see if there are any goods that are immune to the paradox, and of so how.

Government must limit demand

Some economists suggest that government intervention is required to ensure that efficiency gains in technology are not eroded by the rebound effect. This could be in the form of environmental taxes such as fuel duty, with the revenues being invested into further environmental protection projects.

I think this is an area worth exploring and if correct it would suggest that governments must work with industries to achieve environmentally sustainable outcomes.

It does raise some further questions too. If this type of government taxation can break the paradox, have there been any examples of this truly working? If so, does it come at a social cost to the poorest in society by artificially increasing the cost of certain goods? If so, could another form of government intervention such as rationing be a better solution? Did I just suggest rationing?

So where should we begin?

The nature of a paradox is that it’s almost impossible to solve. And yet, if we are to live within our limits and operate businesses and society in an environmentally sustainable manner, then we must solve it.

Perhaps, instead of trying to find a one size fits all solution, we should take it on a case by case basis and look at every technology, product or resource in its unique context. To do this, we could begin by asking the following questions:

Does the Jevons paradox seem to apply in this case? And if not, why not?

If it does, is it inherently a bad thing? e.g. a rebound affect in demand for solar panels may be a good thing

Who benefits from the gains in efficiency? e.g. the business operating the technology, their customers or other stakeholders

How might this efficiency influence their future consumption behaviour? e.g. is demand elastic or inelastic?

How might this change in consumption affect society more broadly? e.g. increased economic growth or the development of new products that consume more resources

Exploring the paradox

In this newsletter I’m on a journey to find out whether sustainable business is an oxymoron. I have a lot more questions than answers at this stage but it’s clear to me that the Jevons paradox is an important phenomenon affecting the true impact that businesses have on society and the environment.

The paradox suggests that the impact of any business, positive or negative, is not solely dependent on the actions of the business itself, but also on complex dynamics within society more broadly.

I also believe it highlights that while resource efficiency should be considered a good thing, it is only one half of the solution. We need to couple technological efficiency with measures to limit rebound effects in society. That is no doubt the harder part of the equation to solve and to do so we will need to look more deeply at human nature itself.

Update: Since this article was published, I have spent some time exploring how the Jevons paradox affects my own business and whether there is a solution to it. To learn about that, read my new article Could sustainable websites increase energy consumption?

Subscribe to Oxymoron

A thought provoking newsletter for curious minds exploring the complex and confusing world of "Sustainable Business"