Over the Christmas period I found myself reflecting on the materialistic nature of this time of year, with its overwhelming focus on consumerism and gluttony. Christmas has drifted a long way from its spiritual and religious roots to become an annual festival of materialism, and as much as I do look forward to it as a beacon of light in the depths of winter, I always find it somewhat jarring that it also seems to represent so much of what is wrong with modern society.

As I pondered this thought over the New Year, I stumbled upon an old radio lecture by Alan Watts called Unpreachable Religion, in which he presents the idea that we may have things back to front. Our modern culture is constantly accused of being interested in absolutely nothing but material values and yet, he argues that we don’t even care about the material world. In the lecture he says;

We feel that the only thing is to go on getting more and more. And as a result of that, the whole landscape begins to look like the nursery of a spoiled child who’s got too many toys and is bored with them and throws them away as fast as he gets them.

… we’re dedicated to tremendous war on the basic material dimensions of time and space. We want to obliterate their limitations. We want to get everything done as fast as possible. We want to convert the rhythms and the skills of work into cash - which, indeed, you can buy something with, but you can’t eat it - and then we rush home to get away from work and begin the real business of life: to enjoy ourselves. And, you know, for the vast majority of … families, what seems to be the real point of life - what you rush home to get to - is to watch an electronic reproduction of life. You can’t touch it, it doesn’t smell, and it has no taste.

You might think that people getting home to the real point of life in a robust material culture would go home to a colossal banquet, or an orgy of lovemaking, or a riot of music and dancing. But nothing of the kind. It turns out to be this purely passive contemplation of a twittering screen.

He goes on to say that;

if you can make any really broad generalization about something so complicated as the civilization of the United States, [it is] that it is fundamentally an anti-materialistic civilization.

At the time, he was talking about the United States where he lived, but I think it’s fair to say that this anti-materialistic culture he spoke of is now the norm in most of Europe and many other parts of the world.

The French priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin famously said that “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience”. In other words, our minds and souls are having a material experience here on Earth. You would imagine that a healthy society would therefore cherish both sides of this duality - the non-physical and the physical. The strange thing about our modern culture though is that we have rejected almost all concept of spirituality and, according to Watts, we have also forgotten the value of the material world, leaving us with nothing that we truly value. No wonder our society and environment are creaking at the seams.

I studied industrial product design and began my career with the intention of designing sustainable products, only to become disillusioned with the reality that few companies actually want to create high quality products that people truly need and love. If I couldn’t design physical things that really mattered, then I thought the next best thing would be to design things that didn’t really exist - digital products. I co-founded a digital agency with the hope that we could help solve the environmental crisis by dematerialising society with digital technology. In the process I have inadvertently contributed to this anti-materialistic culture with its “twittering screens” and learned that the non-physical nature of digital is little more than an illusion that disconnects us from reality.

Perhaps then, it’s time to stop and ask what it would mean to be more materialistic, not less. If we truly valued the material world, surely we would not be mindlessly gulping food, data and Amazon packets. Instead we would savour the wonders of our physical experience. We would care for our material bodies by fuelling them with natural organic foods, fresh air and exercise. We would value real life contact with other humans instead of dematerialising our relationships into WhatsApp messages and virtual meetings. And we would treat our physical possessions with care, treasuring them and passing them down to others.

My most valued material possession is a chest of drawers that my Great Grandfather brought from Hong Kong for my Grandma’s 18th birthday in 1934. One of my earliest memories is holding onto this chest as a toddler and being mesmerised by the ornate scenes carved into its wooden surface, along with the solid brass Buddha that always sat on top. These items not only tell a personal story about my family but are items of real craftsmanship that have lasted for 90 years and will no doubt last for many years more. Such things are the antithesis of our modern throwaway culture in which we resign ourselves to the idea that even the expensive things we buy will probably only last a few years. How many modern products will still be loved and used 90 years from now?

One that springs to mind is the Anglepoise lamp. Launched in the 1930’s it became iconic for its combination of beauty, practicality and durability, with vintage lamps still in demand today. Simon Terry, the great-great grandson of the company’s founder is the current owner of the family business and has reinvented the company for the 21st century while keeping it true to its roots. In a world of fast fashion and built-in obsolescence, today’s Anglepoise lamps are rare examples of timelines design and come with a lifetime guarantee so that just like the originals, they can be passed down to future generations.

This is not normal and it makes me sad that it isn’t. So many modern products fail long before we are ready to let go of them, and those that do last are often cast aside in our rush to keep up with the latest trends or simply to fill our addiction to the dopamine hit of clicking “Buy now”.

Many companies use the excuse that it’s too expensive to design and manufacture truly high quality products. In a capitalist economy, most companies assume that they need to relentlessly cut costs and keep their customers coming back for replacements in order to compete and remain profitable. To some extent this is true, but perhaps it’s a truth that needs to be challenged more. As the saying goes, “buy cheap, buy twice” and yet our anti-materialistic mindsets so often prefer to buy twice than buy quality.

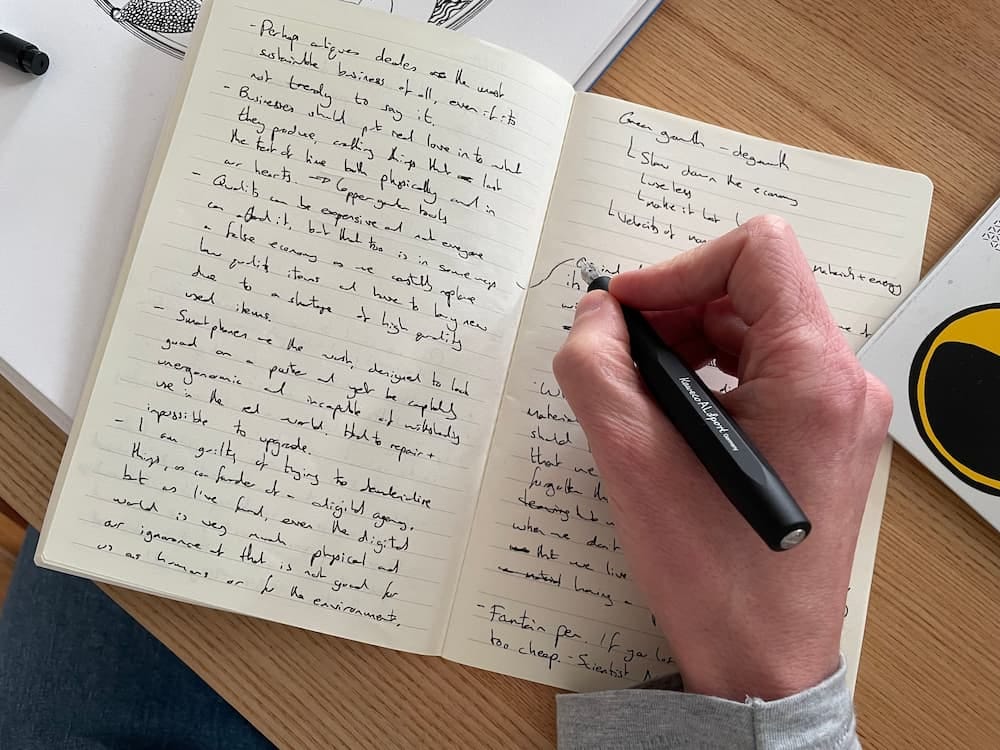

I’m guilty of this. I do a lot of writing and yet since I left school I used cheap ball point pens that regularly broke, got lost or in many cases were designed to be disposable. It always irked me but I had resisted buying a good quality pen on the basis that it seemed extravagant and I was worried about spending a lot of money on an item that I was likely to lose. Then I saw an interview with the scientist Neil deGrasse Tyson in which he commented that if you keep losing your pen, it’s because you don’t value your pen.

His solution?

Buy a more expensive pen!

When I heard this comment it turned my perspective on it’s head. Perhaps I lose my pens precisely because I don’t value them. I set out looking for a pen that I would treasure. It took me a year, but I eventually found a fountain pen that I loved - a Kaweco AL Sport. Designed around 100 years ago and machined from solid aluminium, it’s beautiful, timeless, durable, refillable and repairable. I no longer buy disposable ball point pens and at a cost of about £80, I’ve found it expensive enough that I always know where it is.

Of course, this then raises the issue that higher quality products tend to be more expensive and so not everyone can afford them. This is a valid concern, particularly for daily essentials like food, energy and toilet paper, but when it comes to durable products it might be a red herring. If we had a society in which we truly valued material things, we would also have a thriving economy in the repair and resale of everything from clothing to furniture to electronics. High quality used items would be a preferred and affordable alternative to low quality new items. Not to mention that we would likely have a stronger culture of self-sufficiency in which more of us have the real, physical skills to make and repair things for ourselves.

For businesses designing and manufacturing new products today, the challenge is to find ways of going against the grain and creating things that truly do justice to the physical materials from which they are made, without them being elitist. Products that stand the test of time and will be loved not just for a few moments but for a few generations.

I think Alan Watts is right in highlighting that what we now call materialism is in fact anti-materialism, and yet it is not spirituality. It’s a strange sort of nothingness that leaves us in a vacuum of not really caring about anything.

So which should we choose? Materialism or spirituality?

Of course, this is a false dichotomy.

Instead of choosing one half of our existence and rejecting the other, we need to embrace the wholeness of the human experience.

If we shifted from valuing nothing to valuing the whole, our society would look very different. I imagine that in such a world, instead of craving endless, disposable consumption and watching electronic reproductions of life, we would cherish a few good things and get out there to enjoy the incredible experience of life with our fellow human beings.

As for what this means for businesses, we should remember that they are both creators and mirrors of our culture. No single business alone can create this cultural shift, but they can help create momentum toward it. A good first step could be to create durable, lovable, repairable products that stand the test of time and serve people’s real needs in living a truly good life.

Now, where did I put my pen?

P.S. If you’ve enjoyed this exploration of materialism as it relates to sustainable business, then you might also enjoy my earlier article exploring the other half of this polarity - Is spirituality the missing pillar of sustainability?

I loved your reflection on this subject Tom! I couldn't agree more with the quote from Pierre that we are spiritual beings having a human experience. That means we should value our human interactions over moving away from what makes us humans.

I believe we need to understand the value of the materialistic aspects of life as a way to elevate ourselves as spiritual beings. After all, we won't bring with us everything that belongs to the material world after dying, only what belongs to the spirit, because the spirit is endless.