Are we allowed to question authority?

The remnants of medieval culture may still be holding us back

This week's post looks at the culture of deference to class hierarchy and how it might relate to sustainable business and a healthy society. While it was sparked by something distinctly British, I'd be curious to hear from those of you in other countries as to how you think it might apply where you live. Read on and let me know what thoughts it sparks for you.

A symbol of authority

In April this year, a new little friend of mine arrived to start his life here on Earth. When his parents completed his official registration with the government last week, I got to see his newly issued birth certificate. I always find it interesting to see official documents as they can tell us a lot about an institution or culture, and this one was no different.

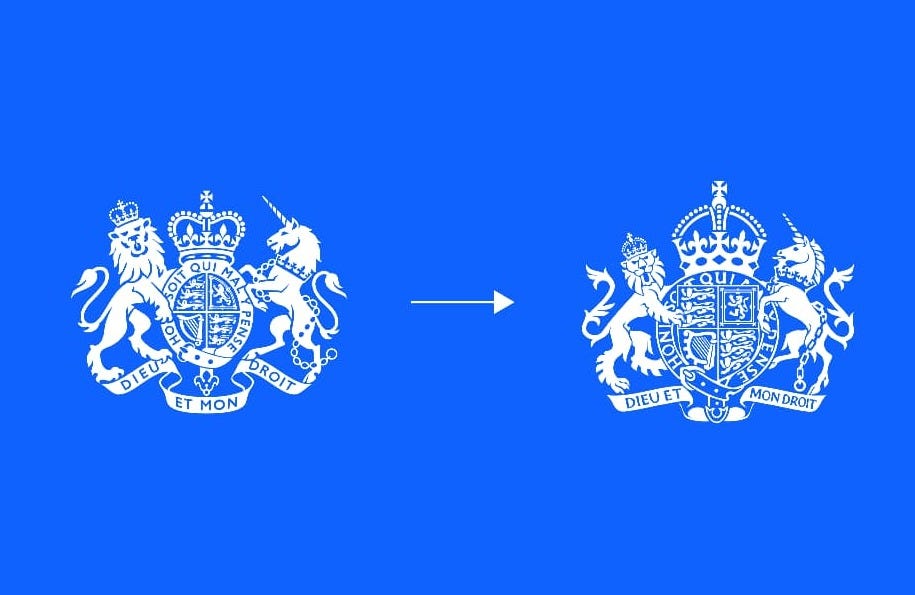

At the top of the certificate was a coat of arms. It’s the kind of symbol that anyone who lives in Britain is used to seeing in all sorts of places, such as historic buildings, courthouses, passports, money and even on the side of mail vans. These symbols are so ubiquitous in British life that most of us barely even notice that they are there. This time though, my wife Vineeta said; “What's that strange symbol?”, followed by the yet more intriguing question, “What are those words written on it?”. And so began a little adventure down an unexpected rabbit hole.

It turns out that the symbol printed at the top of the birth certificate is a version of the Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom, consisting essentially of a shield wearing a crown, wrapped in a ribbon that says, “Honi soit qui mal y pense”. In case you don’t speak medieval French, it means, “Shame on him who thinks evil of it”.

This statement is the official motto of the Order of the Garter, the highest order of chivalry in the United Kingdom, established by King Edward III in 1348. The legend has it that a lady dropped her garter at a ball and the king bent down to pick it up. On noticing judgment from the on looking crowd he declared, “Shame on him who thinks evil of it”, to defend his action and deflect any shame back onto the sniggering onlookers. The symbology of the Garter was then adopted as the emblem of a new order of knighthood, the Order of the Garter, the trusted inner circle of the monarchs allies who pledged unquestionable allegiance in a time when power and legitimacy were constantly challenged.

If it is so deeply tied to the legitimacy of the British monarchy, why then is the motto written in French? The reason for this is that after the Norman Conquest of 1066, French became the language of the ruling class in England and this was still the case when Edward III formed the Order of the Garter in 1348. Laws were written in Latin and French, the nobility spoke in French, and English was seen as ‘peasant speech’.

In this context, the motto says that we must not think evil of the monarchy and aristocracy, as they are a superior class, and those who suspect them should be ashamed of themselves. This makes sense in the context of medieval Britain, but what relevance does it have today?

Deference in modern Britain

In medieval times, the motto and the symbolism of the garter acted as an early propaganda device to protect the rulers against the threat of scandal. It's a rhetorical inversion that says that elites do not have to defend themselves with transparency, reason or even evidence, because those who pose questions are themselves morally questionable.

Nearly 700 years later, this same motto is printed on birth certificates, asserting the unquestionable moral authority of the monarchy and elite classes from the very start of a persons life. Furthermore, it also appears on official court documents in a nation where the courts are supposed to be impartial, highlighting a quiet tension between our modern, multicultural democracy, and the lingering influence of medieval elites.

We could easily dismiss this as a ‘cute’ and irrelevant bit of cultural heritage, but considering that it fundamentally contradicts the supposed values of our modern democracy, the fact that it is still in use should not be so quickly overlooked. It sends a message that good citizens don't rock the boat and that us mere peasants should know our place.

This is as relevant today as ever. In a world that faces environmental, social and economic challenges that threaten people’s wellbeing and ways of life, it’s important that people are able to express themselves. Yet the trend from government in the UK in recent years has been to align with the Order of the Garter’s motto and call shame upon those who do so. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act introduced in 2022 significantly reduced people’s freedom to peacefully protest in the UK and there are an increasing number of cases of it being used to discourage those who question authority.

For example, in July 2024, Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion co-founder, Roger Hallam, was sentenced to 5 years in prison for conspiracy to cause a public nuisance. He was arrested for giving a 20 minute talk on the climate crisis at a meeting for a group planning to block the M25 motorway to gain public attention for looming climate risks. He was apparently not part of the planning or the action itself and yet was given the longest prison sentence in British history for non-violent action. And in May 2025, veteran human rights activist Peter Tatchell was arrested at a Palestine Solidarity protest in London for holding a placard that condemned human rights abuses by both Hamas and the Israeli government. His aim was simply to draw attention to the suffering of all Palestinian victims of violence in the conflict, but the authorities decided to make an example of him.

Despite our apparent freedom of expression in modern Britain, there are many times when people feel afraid to voice their honest opinions in public for fear that instead of promoting open discussion, our society will cast shame upon them simply for opening their mouth.

A very potent example of this is the current situation in Gaza, where many people are afraid to publicly ask questions or even express a pro-peace, humanitarian view, let alone express their horror at the killing of children and what appears to many experts to be a form of genocide. Many fear a backlash against them for voicing unapproved thoughts, or worse still, being accused of being anti-Semitic simply for expressing concern about the welfare of fellow human beings. The culture expressed by the Order of the Garter is still very much alive today. Shame on them who don’t turn a blind eye.

Sadly in our increasingly polarised world, we are not just facing censorship from authorities, but from each other. If we believe in sustainability, then we surely need to encourage a culture of open and respectful dialogue, rather than declaring shame on those who express views that don’t match ‘approved’ narratives.

It’s precisely at times like these when political leaders across the board are failing humanity, that a culture of toeing the line is simply not fit for purpose. Whether it’s environmental issues, poverty, health, culture, humanitarian disasters, or any other issue that we feel is important, we need the freedom to express it openly and engage in dialogue regarding where we want to go and how we might get there.

Renouncing medieval business culture

It might be hard for us to change the wider culture of society, but we can start by changing ourselves and our organisations. For those of us who lead organisations, and anyone who wants to influence the culture where they work, we have an opportunity to reflect on our organisational cultures and evolve them beyond the baseline of society. In particular, by encouraging diversity of perspectives and fostering the psychological safety needed for honest expression.

While the idea of medieval courts might seem far removed from modern businesses, the contrast they provide may be useful to identify areas for improvement. Frederic Laloux’s book Reinventing Organisations presents a useful comparison of organisational cultures that range from the distinctly medieval to those that are increasingly more human and inclusive.

Let’s take a quick look at them:

Red Organisations are strictly hierarchical and fear based, like warring tribes, feudal monarchies and modern mafias. They are destructive and aggressive by their nature and driven by greed rather than any benevolent ideals. These organisations are fundamentally at odds with a healthy society for all, but thankfully few organisations fit that model today.

Amber Organisations are highly structured, formal, and hierarchical, emphasising stability and tradition. While they may have some heritage as Red Organisations, they base their authority on established rules and norms rather than fear. This type of culture is particularly common in the public sector and some long established businesses that were built on strictly hierarchical principles. There may not be anything inherently wrong with an Amber Organisation, but its hierarchical structure and rigidity make it hard for people to fulfil their full potential and difficult for the organisation to adapt to the needs of a rapidly changing world.

Orange Organisations are arguably the most common in today’s economy, operating as meritocratic machines where hierarchy and structure are still fairly rigid. The efficiency of the machine acts as the over-arching priority, with employees able to climb up the hierarchy if they prove their usefulness. New thinking may be encouraged if it drives greater profit but not on purely moral grounds, as the organisation acts as a money making machine. These organisations are more adaptable and do create more opportunities for employees to grow, but they also tend to pursue financial profit at the expense of human and environmental wellbeing.

Green Organisations are what you might call some of today’s purpose led businesses. They emphasise collaboration, equality, and stakeholder value (beyond just shareholders). They do retain some hierarchy but focus on empowering employees and fostering consensus by giving more people a voice. Green organisations value inclusivity and aim to balance profit with purpose, often driven by ideals of fairness and harmony. As such they offer greater opportunity for employees to flourish and attempt to balance financial profit with other objectives, whether they be social or environmental.

Teal Organisations do away with hierarchy and deference altogether in favour of self-management, guided by an evolutionary purpose of the organisation. Employees are encouraged to bring their whole selves to work, integrating personal and professional identities, and the organisation is seen as a living system with a purpose beyond profit. In some ways they represent the peak of organisational evolution, in which humans fulfil their highest potential and play a collaborative role in a society that is socially and environmentally healthy.

I think it’s important to say that even if Teal is the dream, in reality there is no perfect organisational structure or culture, as every organisation has to operate in a unique context. I personally tried to take Wholegrain Digital all the way to Teal and in the end found that it just wasn’t right for us. If I was to summarise why, I’d say that it jumped too far ahead, with employees to a large extent wanting a more stable, hierarchical structure. The sweet spot for us turned out to be predominantly Green, with dashes of Orange and Teal thrown in.

The experience made me question why I felt we needed to get to Teal, rather than just focusing on finding what worked best. In hindsight, the important thing for me was simply that we try to create a culture that values everyone as human beings, treats them with respect, and contributes to the greater whole of society, even if we don’t all agree on everything. It doesn’t sound like much, but its a far cry from the Order of the Garter.

What about your organisation?

If this topic has intrigued you, I’ll leave you with a few questions to ponder about your own organisational culture:

Does your organisation allow everyone to express their views openly? Or are there unspoken limits to free speech?

Does it embrace diversity of perspectives as a strength and source of innovation? Or does it see them as a threat?

Is it open to change? Or is there a rigidity within the organisation that it will fiercely defend?

Does it operate primarily from a place of love and abundance? Or from fear and scarcity?

If nothing else, I hope this article has given you a bit more confidence to express your views truthfully, openly and respectfully, and to support others in doing the same. And on that note, I’d love to hear your views in the comments or on LinkedIn.

Thanks for reading!

P.S. Last week I shared a 13 minute guided meditation with the invitation to envisage the world as you truly want it to be. I’m continuing to invite contributions over the next few weeks, which will feed into a collective vision in the new book I’m writing. If you feel like taking some time to relax and visualise a better world, I think you’ll enjoy it. Big thanks to those of you who have already contributed. Please continue to share it so that I can access diverse perspectives from around the world. Click below for full details.

Can you help create a vision for a better world?

Today’s post is something very different from normal. It’s not an article, but a meditation and a request for your help.

"Rushed to check my kids birth certificates". What a beautiful story. We do need to change this, the UK is not based on a constitution, our rights not enshrined in any document. We are at the mercy of whatever prevailing party is in power and the oveton window can shift to a point where rights we assumed were bedded in rock become on shifting sands. I get why folks in the US fight for free speech as hard as they do.

This is one of the most thoughtful and resonant pieces I’ve read in a long time. 👏 The historical arc from garter to gag order is so sharply drawn — revealing how old myths of power still shape our daily lives, even at the level of birth certificates and boardrooms.

What stood out most to me was the way you wove together institutional analysis with personal, practical reflection — especially the breakdown of organisational cultures. The move from inherited deference (Amber) to inclusive dialogue (Green/Teal) feels both necessary and deeply human.

“It’s precisely at times like these when political leaders across the board are failing humanity, that a culture of toeing the line is simply not fit for purpose.”

This line hit me hard — and feels like a mirror to the systems we’re in.

Your call for psychological safety and the freedom to dissent without shame hits home. In times like these — when nuance is often crushed under pressure to conform — articles like this are a breath of fresh air and a reminder that leadership doesn’t require control, but courage.

Thank you for writing with such clarity, depth, and moral imagination. 🙏

Curious to hear from others: where are you seeing this culture of silence show up in your own work — and what’s helping you resist it?